Tagged: art

Instruction and pleasure

Part two of our look at artwork given to the Stanley Halls by William Ford Stanley. Dr Debbie Challis sheds more light on one of the beauties that once adorned the walls of Stanley Halls gallery.

The Gamekeeper’s Daughter by Valentine Cameron Prinsep.

Oil on panel, 59.5 x 51.7cm. (c) Croydon Art Collection

The Gamekeeper’s Daughter (1875) is by Valentine Cameron Prinsep (1838-1904, known as ‘Val’) who is, arguably, one of the better known of the artists within William Ford Stanley’s original art collection. Val Prinsep was born in India but when his parents Thoby Prinsep and Sara Monckton Prinsep retired to London in 1843 they surrounded themselves with artists and literary figures, particularly from 1851 when they moved to Little Holland House in Kensington. They were joined there the following year by the artist George Frederic Watts who moved in and stayed over 20 years. Val Prinsep decided to become an artist and was at first trained by Watts:

“He was influenced by the salon his mother had established at Little Holland House around Watts. The guests, almost all of whom became Prinsep’s friends, included Tennyson, Thackeray, Browning, Holman Hunt, Millais, Leighton, D. G. Rossetti, and Burne-Jones; Sara Prinsep’s sister, Julia Margaret Cameron, took photographs of the group”. (Dakers, 2004)

As a teenager Val accompanied Watts to the excavations of a Wonder of the World, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus at Bodrum in Turkey during 1856-7. These were being over-seen by Charles Thomas Newton, an old friend of Watts and John Ruskin and later Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum. At the time, Newton described the artists – bar Watts – who were on his digs as lazy and disdainful of the hard work archaeology requires (Newton, 1857).

Val Prinsep may not have impressed the formidable archaeologist, but he soon became an accomplished artist and seemed to be rarely idle. He shared many of William Ford Stanley’s attitudes to education and self-betterment as well as a desire to open up access to art to a greater number of people. Prinsep instructed art students at Worcester College on the progress of art and the need for education in art and nature in 1883. Following Ruskin’s doctrines, he urged the students to look at nature closely and ‘above all learn to draw’ (Prinsep, 1883). Two years later, Val Prinsep was one of many artists from the Royal Academy (others included Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Edwin Long, Hamo Thorneycroft and Alfred Waterhouse) to sign a petition calling for the National Gallery and British Museum to stay open until 10pm three days a week. This 1885 petition revisited a parliamentary inquiry of 1860 on opening hours of national museums and galleries and access to the public, above all access to working people. Evening opening was to provide ‘instruction and pleasure’ to a greater number of people.

The Gallery in Stanley Halls is a memorial to the desire to offer opportunities for education and leisure to people from all backgrounds that Stanley shared with other like-minded Victorians. We hope that it will again become a creative centre for ‘instruction and pleasure’ at the heart of South Norwood.

References

Caroline Dakers, ‘Prinsep, Valentine Cameron (1838–1904)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/35615, accessed 29 May 2013]

Charles Newton, Letter to Antonio Panizzi, 3 September 1857, Britt. Lib. Add. MSS. 36718, f. 194.

‘Important Facts on the Week Evening Opening of Museums’ (1885). Earl Grey Pamphlets Collection, Durham University [www.jstor.org/stable/60227298].

Valentine Cameron Prinsep (1883), ‘An address to the art students of the Worcester School of Art delivered at the distribution of prizes, December 12th 1883’.

The art detectives find Stanley’s feminine side

Our art expert Dr. Debbie Challis gets down and dusty to give a masterclass in Stanley Halls’ artistic heritage, with help from Judith Burden

One of the intriguing aspects of William Ford Stanley’s collection of paintings – that used to be on display in the Stanley Halls’ gallery when it was first opened to the public – is the number of women artists represented. Most are unknown, such as Edith Gillman, but Theresa Thornycroft (1853-1947) belonged to a family of relatively successful artists. Her mother, Mary Thornycroft (1809 -1895), nee Francis, was the daughter of the sculptor John Francis and married one of his apprentices Thomas Thornycroft. Her brother, Sir Hamo Thornycroft, was a sculptor, as was her sister Alyce, who was also a painter along with Theresa and her other sister Helen. Their eldest brother Sir John Isaac Thornycroft, however, bucked the artist career trend and became a naval engineer, founding the Thornycroft Ship Building Company.

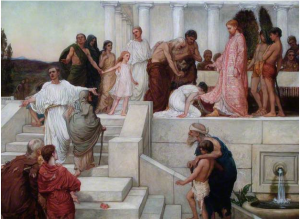

The Parable of the Great Supper by Theresa Thornycroft is a biblically-themed painting depicting the different attitudes, from adulation to suspicion, towards the serene figure of Christ on the night before he is denounced by one of his disciples. The costume and framing of the scene makes it very much in the style of the so-called Victorian Olympian painters such as Alma Tadema and Leighton, but closer observation also traces the influence of Ford Maddox Brown, under whom Theresa trained.

Theresa’s mother was a highly successful artist who produced portrait statues of Queen Victoria’s children and later trained Princess Louisa. Her work provided a steady income, unlike the work of her husband Thomas, and it is likely that Theresa could flourish and train as an artist due to the encouragement of, and example set by, her mother.

It looks likely that Theresa gave up most of her work after marrying Alfred Ezra Sassoon, of the famous Iraqi Jewish dynasty, and having her eldest son Siegfried Sassoon in 1886, who of course became the famous writer, best known for his poetry from WW1. Before the couple separated, Theresa had two other sons, Michael and Hamo, who died in WW1, and she then lived at Matfield in Kent (near Tunbridge Wells).

This is just an overview of Theresa’s life. It would be intriguing to find out more about why Stanley bought this work and whether he knew the family, possibly through her brother.

If you want to see more of the paintings that once graced the gallery at Stanley Halls, have a look here at a previous blog entry.

Further Reading:

Nancy Proctor, ‘Thornycroft , Mary (1809–1895)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/27368, accessed 10 May 2013].

Deborah Cherry (1993), Painting Women. Victorian Women Artists, London: Routledge.

One man’s pile of bricks …….

Budding art critic and SPI Communications Lead, Khris Raistrick, gives his take on the Stanley Hall’s paintings that have recently been cataloged.

‘I don’t know much about art, but I know what I like’. We’ve all heard the phrase, and I’m afraid it most certainly applies to me. I saw a painting in a Finnish art gallery of a woman in a phone booth about 20 years ago that I thought was all right. Near where I used to live in the badlands of New Cross, had it not it dawned on me oh-too-late that the stencil paintings in the nearby tunnels were by Banksy I’d have found someone with a JCB and relieved Lewisham Council of the wall before they painted over them [and yet the somewhat surreal graffiti ‘Yuppies Go Home’ and even more bizarre ‘Kim Wilde’ on nearby walls survived] and I’d now be living in Jersey.

So – I’m a bit of a heathen, though I am sure some of the luminaries on the SPI could explain to me why a pile of bricks is not just a pile of bricks when someone has shoved them on the floor of an art gallery, put a barrier around them, and given them a ‘contextual meaning’. [Actually, I really would like to get a job writing the stuff that goes alongside these works. It usually involves the phrase ‘challenges your pre-conceptions about what art really is’].

Anyway, for those of you who like their art a little more, er, traditional, you might be interested in looking at some paintings that used to hang in Stanley Halls and now line the corridors of Croydon Council, have a look here.

They were painted by eminent artists who were contemporaries of William Stanley. Rumour has it that a number of the original paintings were sold years back by the Council ………Hmm, a quick check on sale prices for some of the artists shown in the link above hint at a great value. A painting by one of the artists, Kosler sold for over quarter of a million sovs.

Let the light shine in. The beautiful brass globes in Stanley’s purpose built gallery complementing the filtered sunlight to show the paintings to their best.

The paintings left Stanley Halls when the ownership passed to Croydon Council in 1934. There were originally 70 works displayed in Stanley’s purpose built gallery, one attributed to Turner. Wonder where that one is now?

Much respect goes to SPI members Debbie Challis and Judith Burden for digging these out of the archives and for cataloguing them.

Perhaps you don’t know much about art but you know what you like – and you might like these. My verdict? I know one thing – it’s ‘proper’ painting. And all part of Stanley Halls’ rich heritage….